Microsoft Surface Pro X And Pro 7 Review: Snapdragon And x86 Experience

|

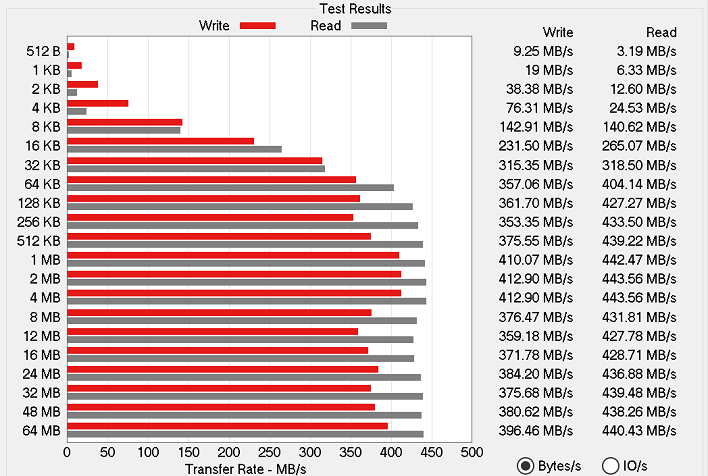

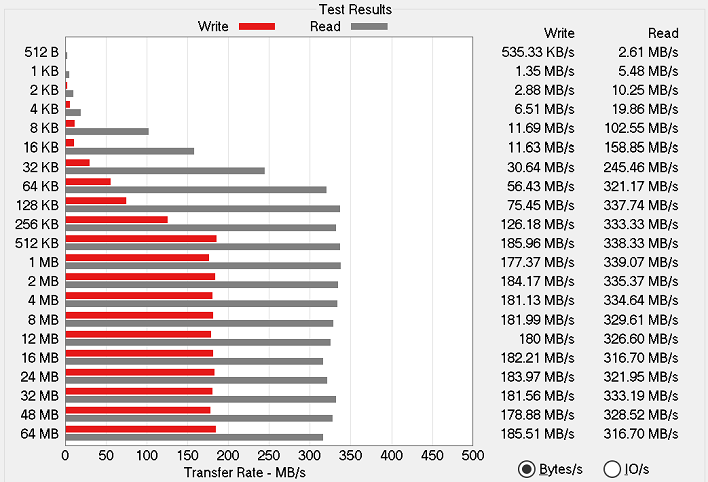

We wanted to get a feel for how other devices performed with the Surface Pro X. To do so, we slapped a Sandisk Ultra II 500 GB SSD into a USB 3.0 enclosure and put ATTO Disk Benchmark through its paces. It may not expose every nuance to the Surface Pro X's USB 3.0 controller, but it should give us an idea if there are any compromises.

It's true that ATTO is a native x86 application, but the internal SSD of the Surface Pro X hit its specified speeds. Unfortunately, the same can't be said for the USB 3.0 controller on the Arm convertible. The drive routinely hit around 75% of the read performance of the same drive on the Surface Pro 7, and more embarrassingly, only 50% of the write performance. It's definitely faster than USB 2.0, but this performance is not getting the most out of our drive setup. Because the internal drive did so well relative to its specifications, we don't think the lack of Arm native benchmarks caused the performance hit. Further, it's possible Microsoft can remedy the softer USB-C performance of Surface Pro X, with a future firmware or driver release.

|

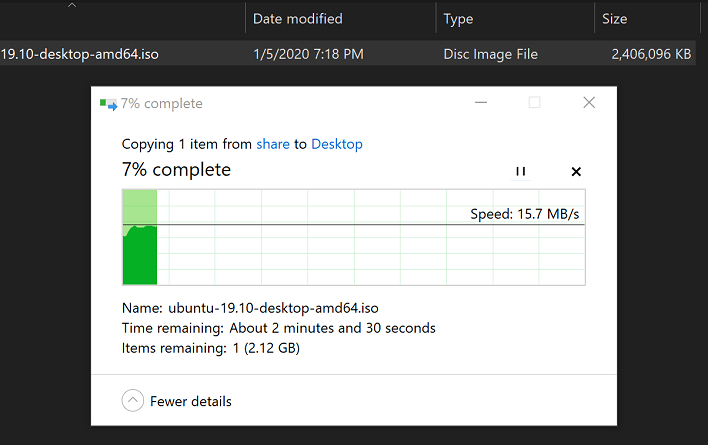

Microsoft's Surface Pros have different Wi-Fi capabilities. The Surface Pro 7 has an Intel 802.11ax Wi-Fi 6 module, whereas the Surface Pro X relies on Qualcomm 802.11ac built into the SQ1 SoC. To test transfer rates, we connected both devices to our Wi-Fi router (a TP-Link Archer C7 running the latest stable DD-WRT custom firmware) and transferred the 2.3 GB Ubuntu 19.10 ISO image file to and from the machines. We set up the Surface Pros around two meters (just under seven feet) from the router and tested each separately.

Both Surface Pros connected to an SMB share on a desktop PC with a Core i5-9600K and an MSI MPG Z390 Gaming Plus, which has an Intel I219-V Gigabit Ethernet controller. We used a stopwatch to time the transfers to find the average transfer speed. First we pulled the file from the host machine, renamed it, and then copied it back. The share is on a Corsair Force MP510 960 GB SSD, so the only test here is whether the Surface Pros' wireless network adapters could keep up.

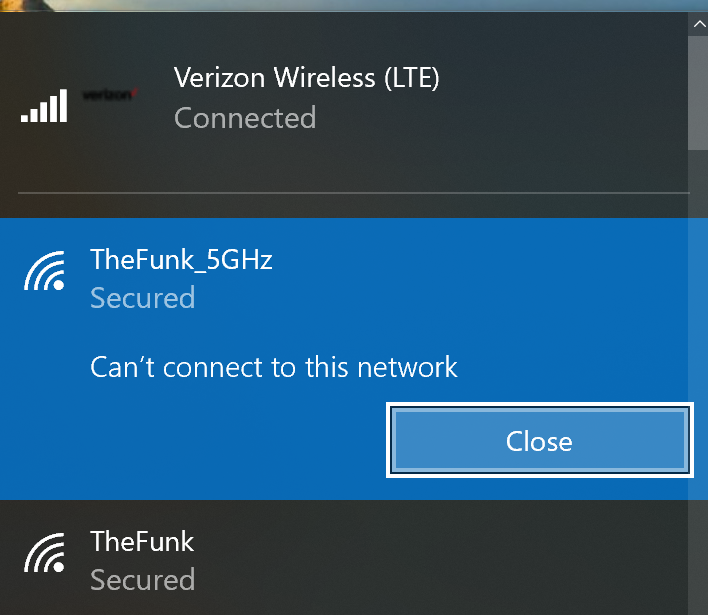

The Surface Pro X had a bit of trouble with our 5 GHz 802.11ac network and just refused to connect. We made sure Windows had the latest updates, rebooted the machine a couple of different times, and stood on one foot while holding our noses but nothing worked.

The Surface Pro 7 transferred the file just like we expected. The file sped along at around 33 MB per second and finished transferring in 73 seconds. That works out to be 260 megabits per second, which is about as good as we've ever seen out of this router in practice. Uploading the file back to our network share was almost as fast, and finished transferring in 79 seconds at around 31 MB per second.

The Surface Pro X refused to join our 5 GHz network but maintained strong Gigabit LTE connectivity

TP-Link advertises the Archer C7 to run as fast as 1.75 Gigabits per second on the 5 GHz network and 450 mbps on the 2.4 GHz network, but we've never seen anything close to that since there are several smartphones and other devices on that network. We're interested in real-world scenarios, and it's very rare that a single device will be the only wireless device on any given network, so this certainly seems real-world.

Wi-Fi isn't the only network the Surface Pro X has at its disposal, however. We also took it for a spin on cellular data, as outlined earlier. While the 4G modem in the device can handle up to gigabit speeds, Verizon's network just isn't fast enough to provide that kind of throughput in central Illinois. Still, we saw 4G speeds on par with an iPhone 11 Pro. Both the Surface Pro X and the iPhone maxed out at around 65 megabits per second for downloads and 15 megabits per second on the upload. We had no problem with connectivity while traveling into Iowa, and the signal was solid throughout our trip.

Battery Life

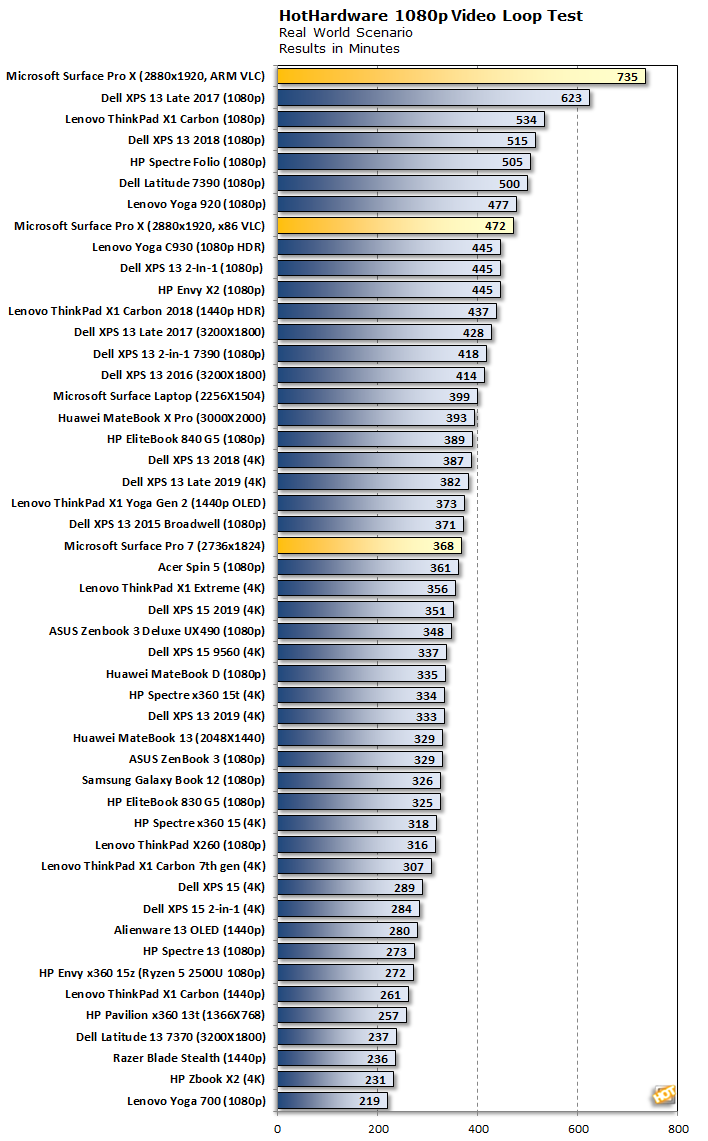

Anecdotally, we've already established that battery life for the Surface Pro X is simply outstanding. We got four full days of light to medium use out of the system while we traveled, prepared baked goods in the kitchen, and watched videos. However, we can quantify battery life just like we always have: with our custom 1080p video playback test with VLC.An interesting thing happened when we tested battery life. Our playback test didn't go as well as we'd expected. Battery life was very good, but it wasn't what we expected after traveling with the system for a long weekend. Then it hit us: we test with a slightly older version of VLC, and the Surface Pro X was playing back the video with x86 emulation instead of natively. Our theory was that x86 emulation requires more processing power and therefore harmed the Surface Pro X's battery life. So we grabbed the latest Windows Arm build from VideoLAN's website and started our test over. We'll let the results speak for themselves.

Holy moly. We got more than thirteen hours of video playback out of the Surface Pro X while using a native version of VLC, but lost quite a bit of that with the older build. Even then, battery life is very good. Very few PCs can play back video for nearly eight straight hours, let alone a two-in-one that weighs less than two pounds. That thirteen hour figure, though, that's just crazy. Battery life on the Surface Pro X is phenomenal with the caveat that you're using Arm native applications. Once you introduce an x86 app to the equation, battery life falls back down to merely just excellent.

That's really the rub with the Surface Pro X. There's a ton of potential in the Windows on Arm platform. Even high-performance Arm SoCs like the Qualcomm SQ1 (a custom-tuned version of Snapdragon 8cx for Microsoft) can provide amazingly low power consumption under the right circumstances, but the frustrating part right now is that the software ecosystem just isn't there yet.

If you live online in a browser and maybe play back local video, you're covered. But as soon as you go into offline Microsoft Office work, photo editing, or just about anything else, performance softens, both in terms of battery and actual processing throughput. This has the potential to be a really great platform for business users on the go, but without native apps, Surface Pro X has to work harder to get there.

Thermals and Acoustics

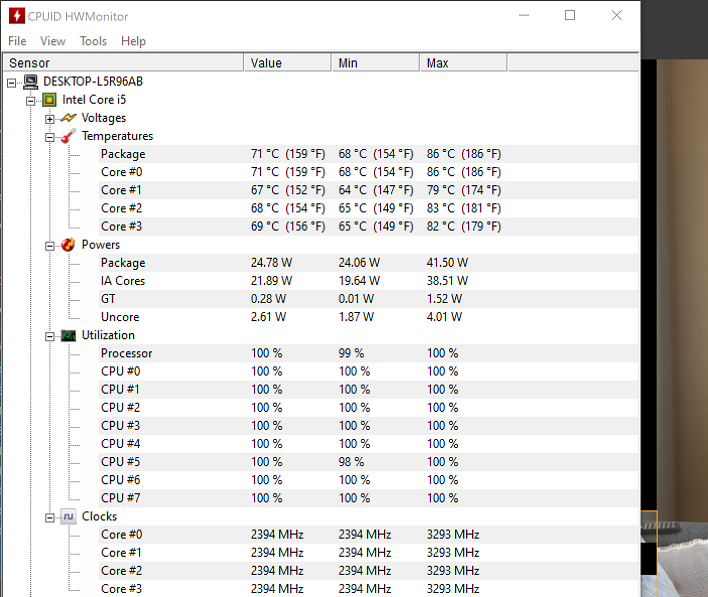

The Surface Pro X and Surface Pro 7 are both totally fanless beasts. As a result, there is no fan noise, which is a beautiful thing. Working in total silence (or at least working without listening to a whining fan) is extremely freeing. However, under a sustained load, performance can really suffer. For example, the Dell XPS 13 2-in-1 with the Core i7-1065G7 that we reviewed recently earned a mark of 1803 in Cinebench R20. The Surface Pro 7's Core i5-1035G4 could only muster 1160, more than a 35% delta in performance.

The reason for this is that the Surface Pro 7 manages thermal performance quite well. At the start of the run, the CPU was allowed to hit around 85 degrees Celsius or so while running at upwards of 3.2 GHz. Very quickly, however, the system trimmed back the CPU speeds and the CPU temperature settled in at 59 to 60 degrees Celsius while finishing the run at 1.9 GHz. The center rear of the system gets pretty warm to the touch, but not uncomfortably burn-your-hand hot. We think that this sort of thermal management was the right call, but it's the price of total silence.

The Surface Pro X could run many temperature monitoring apps that we could find, but they all relied on x86 compatibility mode and as a result couldn't show any temperatures or even display the proper CPU. The window in HW Monitor showed Virtual Processors and no temperature information except for the SSD. The same was true for CoreTemp and SpeedFan. The Surface Pro X couldn't run any of our heavy load apps, either, so it wasn't really possible to stress the CPU the same way we could the Surface Pro 7. As a result we have some pretty incomplete data, but the system only ever got barely warm to the touch in extended use case and formal benchmark testing.