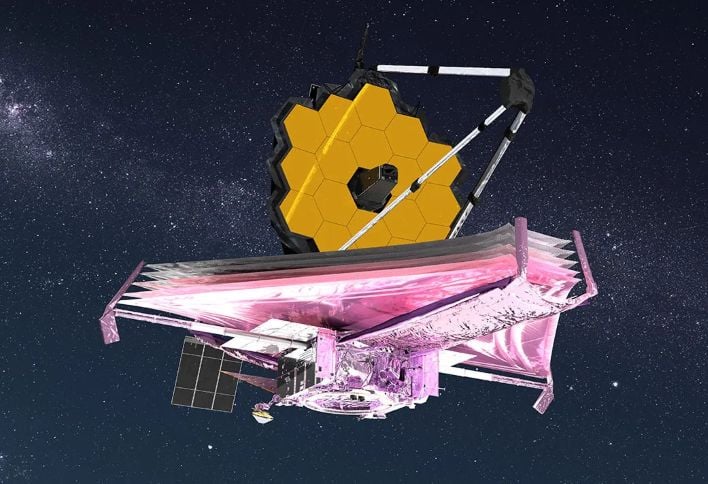

A team of Pennsylvania State University researchers has a unique take on mysterious red dots first observed by the

James Webb Space Telescope. Initially thought to be tiny, crimson galaxies, the red dots are now proposed to be a new and exotic class of celestial object: a hybrid of a black hole and a star, which researchers have dubbed "black hole stars."

Since their

discovery in 2023, astronomers have been puzzled by these little red dots, i.e. extremely bright, compact objects that appear far more luminous and ancient than they should be, given their distance. The dots, which glow with an intense crimson light, were an unexpected discovery and have since challenged conventional models of galaxy formation. The new theory suggests that these aren't nascent galaxies at all, but rather colossal star-like structures with a

black hole at their core.

A black hole star isn't a binary system though; it’s a single, unified object. According to the hypothesis, these objects formed in the early universe when a nascent black hole was born within a massive cloud of gas. As the black hole in the center draw matter in, it converts the gas into energy which then emits light.

"We looked at enough red dots until we saw one that had so much atmosphere it couldn't be explained as typical stars," said Joel Leja, an associate professor of astrophysics at Penn State and a co-author of the study. Leja explains that he believed the team was looking at a tiny galaxy with many cold stars, but instead, the evidence points to a single, gigantic, and very cold star being powered by an interior black hole.

The existence of these black hole stars, if confirmed, could provide a missing link in the

rapid growth of supermassive black holes found at the centers of today's galaxies. They could represent the infancy stage of these cosmic engines, demonstrating a method for black holes to grow at a rate far faster than previously thought possible.

For next steps (and to obtain a more definitive answer), the research team intends on testing the density of the gas within this hybrid black hole/star. But the team is

remaining open-minded about it all. Leja concludes, "It’s okay to be wrong. The universe is much weirder than we can imagine and all we can do is follow its clues. There are still big surprises out there for us.”

Main photo credit: T. Müller/A. de Graaff/Max Planck Institute for Astronomy