Carnegie Mellon's Camera Lens Breakthrough Eliminates Background Photo Blur

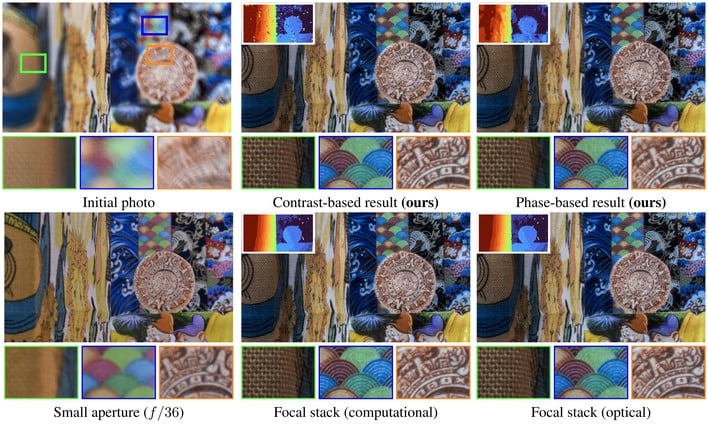

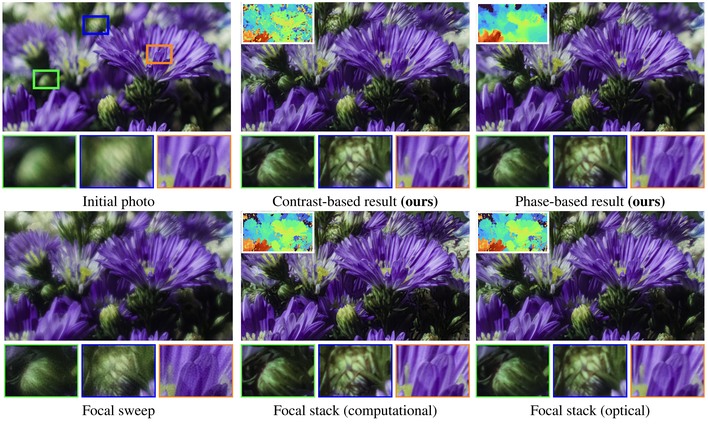

To understand why this matters, you need to understand what most cameras do today. A standard lens focuses light onto a flat sensor. If something isn't sitting exactly on the focal plane, it turns into blur. You can shrink the aperture to increase depth of field—that is, to bring more of the image into focus—but that costs light and sharpness. Alternatively, you can take many photos at different focus distances and stitch them together later, which works well... as long as nothing moves in the meantime.

What CMU's team has built is different from these two methods. Instead of one global focus setting, their camera can vary focus across the image. One pixel can be focused on something close, another on something more distant, and yet another on something far away, all at the same time. They accomplish this using a programmable optical system based on something called a "Split-Lohmann lens." No, it's not a classic prog rock album; it's actually a clever setup involving phase plates and a spatial light modulator. It's basically a screen that can bend light differently at each point. By carefully controlling how light is delayed as it passes through the system, they can tell different parts of the image to focus at different depths.

The result is what they call spatially varying autofocus. It's like giving every region of the image its own autofocus motor. To make this work in real scenes, the system has to figure out how far away things are. The researchers devised two methods. One is "contrast-based autofocus," where the camera slightly varies focus and watches which areas become sharper; this is the same idea used in traditional cameras, but applied locally across the image. The other is "phase-detection autofocus," where, by comparing tiny differences between paired pixels, the system can estimate depth and adjust focus almost instantly.

Once it knows the depth map, the camera reshapes its focus field to match the scene. The final image comes out fully in focus, with no post-processing required. That's the key difference from existing "all-in-focus" techniques. Light-field cameras, focus stacking, and AI-based deblurring all trade off resolution, introduce artifacts, or require multiple frames. This system keeps full optical sharpness, and it works in real time.

Even more interesting: the researchers can intentionally shape the depth of field. This allows them to simulate tilt-shift effects, blur only specific objects, or even remove thin near-field obstructions (like wires) by focusing past them optically; no Photoshop tricks required. There are limitations, of course; the current prototype is bulky, and inefficient with light. Still, the implications are big. This kind of technology could reshape photography, microscopy, machine vision, and even mixed-reality displays, where matching human visual perception is critical.