Researchers Dig Up Galactic Graveyard Of Milky Way's Dead Stars And Map It Out

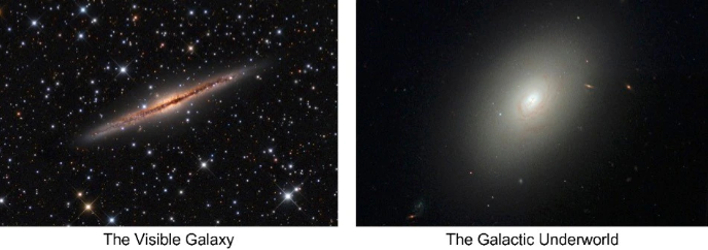

The Milky Way as we know it is a crowded space. A black hole weighing 4 million times that of our Sun lies in the center, with millions of stars swirling around it at break neck speeds. However, there is a galactic underworld that exists, which is comprised of the "corpses of once massive suns that have since collapsed into black holes and neutron stars," according to a new study from the University of Sydney that has created the first map of this graveyard in space.

"These compact remnants of dead stars show a fundamentally different distribution and structure to the visible galaxy," remarked David Sweeney, a PhD student at the University of Sydney and lead author of the paper recently published in Monthly Notices of the Royal Astronomical Society. He added, "The 'height' of the galactic underworld is over three times larger in the Milky Way itself. And an amazing 30 percent of objects have been completely ejected from the galaxy."

Neutron stars and black holes are what make up some of our most intriguing science fiction novels and movies. These entities are created when massive stars exhaust their fuel and then suddenly collapse. The aftermath is a "runaway reaction that blows the outer portions of the star apart in a titantic supernova explosion." As this occurs, the core continues to compress in on itself until it either becomes a neutron star or a black hole, which warp space, time, and matter around them.

It is thought that billions of these have formed since the galaxy was in its infant stages, and since been thrown into the darkness by the supernova that created them. Now, researchers have been able to recreate the full lifecycle of these ancient dead stars, and map out where their remains lie.

"One of the problems for finding these ancient objects is that, until now, we had no idea where to look," stated Sydney Institute for Astronomy's Professor Peter Tuthill, and co-author of the paper. "The oldest neutron stars and black holes were created when the galaxy was younger and shaped differently, and then subjected to complex changes spanning billions of years." Tuthill says it has been a monumental task to model all of this in order to find them.

The researchers say that the most exciting part is still ahead. Now that they know where to look, observatories like the James Webb Space Telescope and Hubble Space Telescope can begin searching for them. Sweeney and Tuthill are both optimistic that the 'galactic underworld' will not stay "shrouded in mystery" for much longer.