Study Finds Alarming Dark Patterns Of Deception In Crawl Of Thousands Of Shopping Sites

In total, more than 1,200 of the 11,000 online shops that Princeton crawled found some form of deceptive practice. The list of crawled sites includes the biggest names in retail, including Amazon, eBay, Walmart, Target, and more. Because of the intervening 15 months since the study, the exact list of what Princeton calls "dark practices" may not be totally up to date. However, the study does dig into what those specific practices entail, which makes it interesting and informative for the average shopper today.

Caveat Emptor When Shopping Online

Princeton's study breaks various practices into seven basic categories in a wide range of actions against which buyers should protect themselves. It all starts with the concept of Sneaking, a practice to artificially inflate the cost of shopping. This can be a very straightforward automatic bundling of goods. For instance, Princeton found a flower shop that added a greeting card to the cart every time a buyer picked out a bouquet. Sneaking also applies to hidden costs, which mostly take the form of vague "handling" fees. Stores that advertise a subscription service but frame it as a one-time cost also qualifies as Sneaking.Urgency and False Scarcity are two of Princeton's categories that really fall into the same bucket. Many websites had timer overlays on the home page showing a special price for a limited countdown time, which often varies from 30 to 60 minutes. The study found that long after the timer expired on these supposed offers on various websites, pricing on affected items hadn't changed. That's just an outright lie in our book. Scarcity practices try to goad buyers into purchasing items quickly by showing that only a few are left in stock or that an out-of-stock item "just sold out," even if it's been that way for days or weeks.

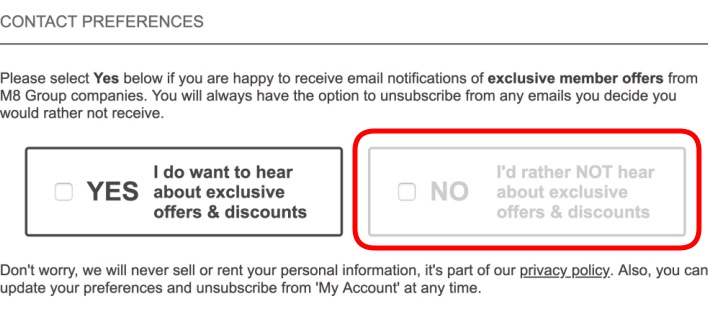

This opt-out option highlighted in red wasn't actually disabled, but you'd be forgiven for thinking that it was.

Misdirection and Social Proof also go hand-in-hand as methods that try to steer user decisions based on outside forces. Misdirection might just be something as simple as confirm-shaming, in which the user who wants to pass on a special offer has to click a button that says, for example, "No thanks. I like full price." Visual interference can just be disguising a "decline" option. One particularly egregious example Princeton shared was a decline button that appeared to be disabled. This can be seen outside of shopping sites, too. Microsoft did something similar every time a user tried to switch the default browser in Windows 10 from Edge to something else, though recently that prompt has changed to be more clear.

Social Proof is a specific misdirection practice in which sites show shoppers others online who are "buying" items. These are unverifiable claims that should not sway you into buying things just because a site says other people are. Princeton also helpfully provides a table of third parties who enable Social Proof activities on storefronts, so those other buyers shown by a page may not even be on the same website. Every eBay listing that shows how many other buyers are watching an item uses Social Proof to try to encourage people browsing to buy right away.

The last group of practices encompasses includes Obstruction and Forced Action. Obstruction most commonly makes the task of canceling a membership cumbersome. If you have to contact customer service to cancel an order or end a subscription that you could set up online without any human intervention, that's Princeton's definition of classic Obstruction. It's not hard to put a Cancel button on a website, but the retailer is hoping that people have too much social anxiety to talk to a person. Meanwhile, Forced Actions make the user do something tangentially related to a task to get the desired action completed. Anybody who has ever signed up for an account and had to agree to accept marketing emails in the process has fallen victim to this deceptive practice.

How can shoppers protect themselves?

The best way to not fall prey to deceptive shopping practices is to know what they are and learn to identify them. If a listing says that an offer is only good for a limited time, but doesn't specify what that time limit is, there's probably not any rush. A sad truth of all retail, not just limited to online stores, is that some shops will do anything from bending the truth to stopping just short of an outright lie to make a sale. Doing some research before buying and eyeing every listing with a healthy dose of skepticism are two great ways to protect yourself from sharks online.The good news is that some retailers have changed their ways after being called out in this study. For example, Musician's Friend, which is part of music shop giant Guitar Center, no longer requires users to sign up for emails when creating an account. Other shops have not changed their ways, however. WSJ Wine still hides the fact that its Advantage program is a $90 subscription with automatic renewal unless shoppers click through not one but two pop-up screens.

Princeton's web crawler has a GitHub repository setup with all the scripts and resulting data for perusal, which the researchers linked on the study summary page. We encourage all of our readers to get to know how these practices work so that you can protect yourselves from falling victim. Happy shopping, and caveat emptor.