Microsoft Warns Of Sophisticated Android Ransomware That Hijacks Your Home Button

Unlike ransomware that hits Windows machines, Android devices rarely actually get their data encrypted. Instead, a malicious app will present itself when the phone gets locked, blocking access to apps and data. One of the first methods was using an Android special permission, which users unwittingly granted when they installed the app from an app store. Back in the pre-Lollipop (Android 5) days, apps just always got all their permissions at install time. It works differently today in part to thwart this kind of attack vector.

What are attackers doing now? They're still misusing system-level functionality, but in new and interesting ways. First, it registers itself as a handler for a whole bunch of system activities. Everything from a Boot Completed event when the user first starts the phone to a ringer mode change or unlocking the device will notify the ransomware what's going on with the system so it can present itself. All it has to do is get the user to interact with it one time so it can execute. It'll try to do that through alerts, system windows, accessibility features, or other ways that users interact with their phones. We'll examine what seems to be the most common attack vector, though: notifications.

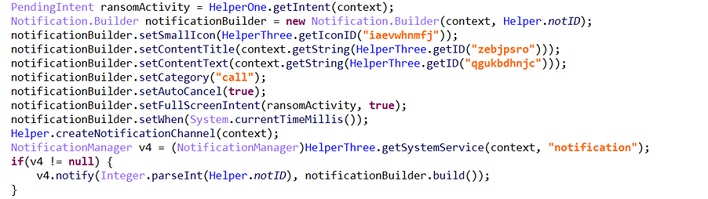

Several alert types on Android interrupt all activity and require immediate user interaction. For instance, when you receive a phone call, that notification is full-screen and requires immediate action. Malware authors figured out they could build a notification that requires immediate interaction. The malware creates a full-screen notification using the Notification Builder API and displays it to the user. Once the user interacts with that notification, the hard part of getting their attention is over. That's just the notification, though - next, we have to get the user to interact with it. One way that the user is always going to interact with their phone is the Home button, so the attacker just has to convince the user to leave the notification.

Without getting too far into the Android app development weeds, Android apps live in Activities. Each screen in an Android app is its own Activity, which is derived from a base class. That base class has methods (functions) that get called when certain events happen. One of those events is detecting when the app is about to get backgrounded, called onUserLeaveHint(), which fires when the user tries to leave an activity or send it to the background. For instance, when pressing the Home button. Because it's defined in the base Activity class, developers are free to override it with their own functionality. In this case, that functionality is the ransom message. Now your phone is locked up.

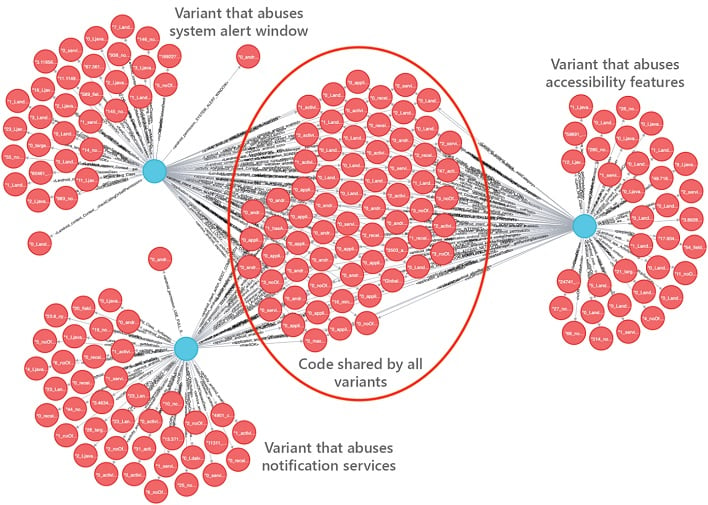

Microsoft used a mix of machine learning and hands-on forensics to track down the behavior. Attackers try to hide their intentions and cover their tracks in many ways. The first and most obvious is by excluding key pieces of the Android manifest. Attackers also have their malware apps decrypt garbage data to try to fool researchers into thinking it's integral to the attack. There's also an encrypted dex file (Dalvik VM executable) that hides away the malware payload. By encrypting both garbage and real app code, it makes it harder for researchers to pin down what's happening. These guys are sneaky, for sure.

Microsoft says its enterprise Defender for Endpoint software can detect this kind of behavior and prevent bad actors from locking down a device. We should all be careful installing unknown apps, too. It seems like a day doesn't go by that Google isn't banning new apps from Google Play, and it's going to require increased vigilance on the company's part to find these new attack vectors and squash them.