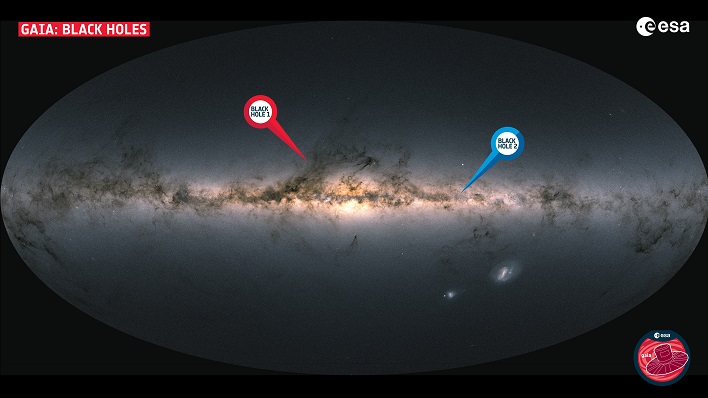

Wobbling Stars Reveal Two Black Holes Closest To Earth Unlike Any Ever Seen

As a team of astronomers observed the orbits of stars tracked by Gaia, they noticed that a few of them seemed to wobble, as though they were being gravitationally influenced by massive objects, according to a recent blog post by ESA. After being unable to find any light associated with the objects, the team was left with only one possibility, black holes.

"What sets this new group of black holes apart from the ones we already knew about is their wide separation from their companion stars. These black holes have a completely different formation history than X-ray binaries," remarked Kareem El-Badry, the researcher at the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics who discovered the new black holes.

The research indicates that in both cases, "the objects are approximately ten times more massive than our Sun." Being neither seem to emit any source of light, other explanations, such as double-star systems, were ruled out.

"The accuracy of Gaia's data was essential for this discovery. The black holes were found by spotting the tiny wobble of its companion star while orbiting around it," explained Timo Prusti, ESA's Gaia project scientist. "No other instrument is capable of such measurements."

Yvette Cendes, an astronomer who helped detect the Gaia BH2, says that the new discovery is incredibly valuable because it tells them a lot about the "environment around a black hole. The fact that the researchers did not see any radio light, indicated that the black hole is not a "great eater and not many particles are crossing its event horizon."

"This is very exciting because it now implies that these black holes in wide orbits are actually common in space - more common than binaries where the black hole and star are closer. But the trouble is detecting them," Cendes stated. "The good news is that Gaia is still taking data, and its next data release (in 2025) will contain many more of these stars with mystery black hole companions in it."