NASA’s Webb Telescope Solves Riddle Of Galaxies Being So Big They Break The Universe

In the two years since Webb began sending back images of deep space, it has tantalized with spectacular imagery such as the Penguin and the Egg, the Carina Nebula, and the Crab Nebula. The space telescope has also had a hand in helping spot exoplanets light-years away. It’s ability to view space in ways no other telescope has before may also be helping to solve the “crisis in cosmology,” or the debate on how quickly the universe is expanding.

The study remarked, “These higher abundances can be explained by modest changes to star formation physics and/or the efficiencies with which star formation occurs in massive dark matter halos, and are not in tension with modern cosmology.”

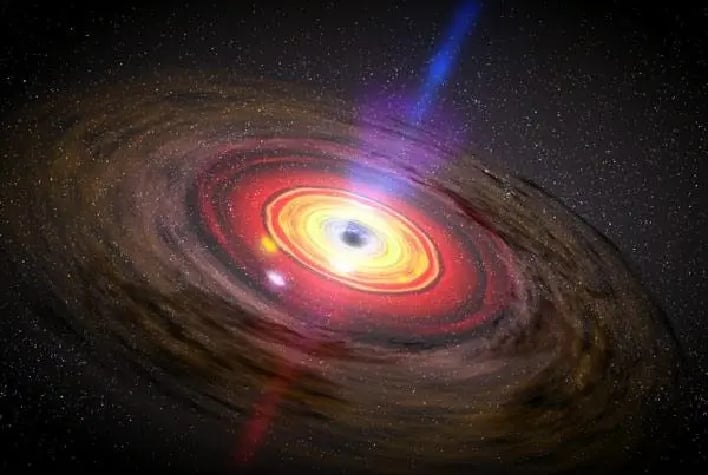

According to the study, the galaxies that appeared too massive likely host black holes that are rapidly consuming gas. Friction in the fast moving gas gives off heat and light, making the galaxies appear much brighter than if that light emanated from just stars. The extra light could be making it look like the galaxies contain more stars, and hence are more massive than otherwise estimated. When scientists remove these galaxies, referred to as “little red dots,” from the analysis, the remaining early galaxies are not too large as to fit within predictions of the standard model.

“So, the bottom line is there is no crisis in terms of the standard model of cosmology,” remarked Steven Finkelstein, a professor of astronomy at UT Austin and study co-author. “Any time you have a theory that has stood the test of time for so long, you have to have overwhelming evidence to really throw it out. And that is simply not the case.”

While the evidence may have settled the main concern, there is still another problem, which is there are still roughly twice as many massive galaxies in Webb’s data of the early universe than expected from the standard model. The researchers suggest one possible reason for this is that stars formed more quickly in the early universe than they do today.

“Maybe in the early universe, galaxies were better at turning gas into stars,” remarked Chworowsky.

As Webb may be helping to clear up the debate on how quickly the universe is expanding, it also raises new questions. “Not everything is fully understood,” Choworowsky explained. “That’s what makes doing this kind of science fun, because it’d be a terribly boring field if one paper figured everything out, or there were no more questions to answer.”