NASA Takes A Deep Dive Into Uranus And Solves Gassy Giant's Hidden Secrets

NASA’s Voyager 1 and 2 are the only spacecraft ever to operate outside the heliosphere, or the protective bubble of particles and magnetic fields generated by the Sun. However, before beginning its journey to interstellar space, Voyager 2 was the only spacecraft to visit Uranus and Neptune.

As Voyager 2 passed by Uranus, it caught an unprecedented view of the strange, sideways-rotating outer planet. Along with finding new moons and rings, it also provided data that has baffled scientists ever since, such as the energized particles that surround the planet, defying their understanding of how magnetic fields work to trap particle radiation.

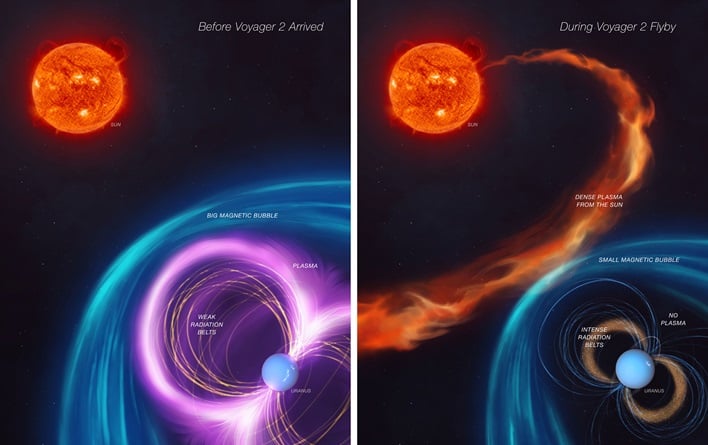

“If Voyager 2 had arrived just a few days earlier, it would have observed a completely different magnetosphere at Uranus,” explained Jamie Jasinski of NASA’s Jet Propulsion Laboratory in Southern California and lead author of the new work published in Nature Astronomy. “The spacecraft saw Uranus in conditions that only occur about 4% of the time.”

What perplexed scientists was the fact the Voyager 2 data indicated inside the planet’s magnetosphere were electron radiation belts with an intensity second only to Jupiter. However, there were no apparent sources of energized particles to feed those active belts. NASA added that the rest of Uranus’ magnetosphere was nearly devoid of plasma.

The missing plasma only added to the mystery, because scientists knew five major Uranian moons in the magnetic bubble should have produced water ions, as icy moons around other outer planets do. The data led scientists to conclude the moons must be inert with no ongoing activity.

The new data analysis, however, points to solar wind as being the cause of there being no plasma observed, and what was occurring to the radiation belts. Researchers now believe when plasma from the Sun pounded and compressed the magnetosphere, it most likely drove plasma out of the system. An intense solar event would have also briefly intensified the dynamics of the magnetosphere, which in turn would have fed the belts by injecting electrons into them.

The new findings may also mean the five major moons of Uranus might be geologically active after all. The researchers stated it is plausible that the moons actually may have been spewing ions into the surrounding bubble all along.

“The flyby was packed with surprises, and we were searching for an explanation of its unusual behavior,” remarked JPL’s Linda Spilker. “The magnetosphere Voyager 2 measured was only a snapshot in time. This new work explains some of the apparent contradictions, and it will change our view of Uranus once again.”