New E5 Xeons Aim For the Cloud; Introduce New I/O Capabilities

Intel launched its new Xeon E5 family today, based on the Sandy Bridge-EP processor. The new chips fill a gap in Santa Clara's product line; the company's Xeon offerings are now Sandy Bridge top-to-bottom. If you've followed the launch of Sandy Bridge and Sandy Bridge-E you'll be familiar with most of the E5 family's new features, but there are a few server-specific enhancements to discuss.

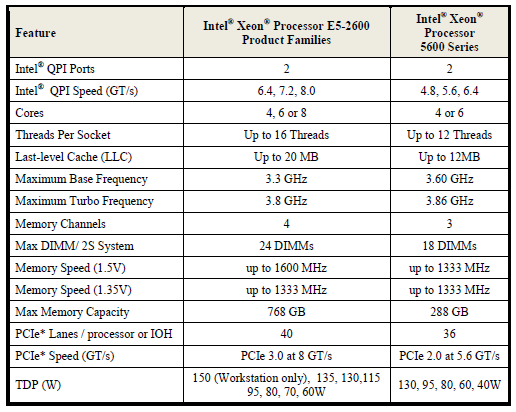

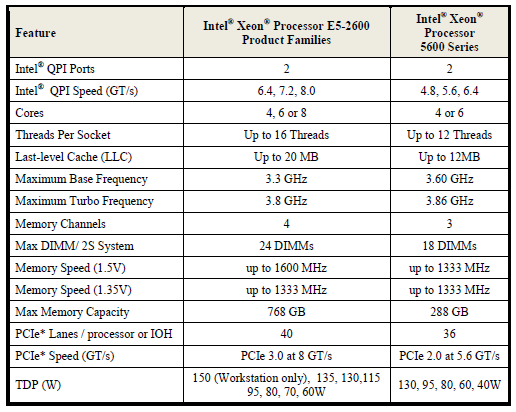

The E5 family uses the LGA2011 socket that Intel launched last fall with Sandy Bridge-E, and as we expected, there's another two cores of creamy smoothness and an extra 5MB of L3 cache lurking in that silicon. The new Xeon platform, Romley, offers up to 24 DIMMs in total in a 2S system, supports both DDR3-1667 and low-power DDR3 1333 (1.5v and 1.35v operating voltages respectively), includes PCIe 3.0, 40 PCIe lanes in total, and operates between 70-150W. That last figure is notable because it's been a long time since Intel released a chip with a TDP higher than 140W; the E5-2687W is an eight-core, 3.1GHz part with 20MB of L3 cache. The "W" means its a workstation-only chip.

The major feature of the new E5 chips is their support for what Intel calls DataDirect I/O. Up until now, network controllers resided off-die and communicated with the CPU via the PCIe bus. With the E5, Intel has created an interface that allows the network controller to drop data directly into the CPU's L3 cache, significantly reducing communication latency. Intel claims an I/O device can read data in 230ns compared to 340ns for Westmere. PCIe 3.0 is also touted as a major advantage, though the evidence is less clear. According to the fine print on Santa Clara's benchmark results, the E5-2680 is 3x faster in a 50% Read/Write 512B benchmark when using 64 lanes of PCIe 3.0 (66GB/s) compared to an X5670 Xeon with 32 lanes of PCIe 2.0 (18GB). Given that the E5 family only supports 40 PCIe lanes, the practical benefit will be somewhat less.

Intel is pushing the E5 family as a cloud server product, which makes this an opportune time to address some of the confusion around that word. Head over to SeaMicro, the server vendor AMD just acquired, and you'll find plenty of mentions of cloud servers -- but SeaMicro's products were built around Intel Atom. Similarly, a great deal of discussion around so-called "wimpy" cores and cloud computing focuses on everything from miniscule mesh processors (Tilera) to the HP/Calxeda initiative. Now here's Intel, claiming that 95-140W chips also qualify as 'cloud' products.

This is what happens when marketing divisions collide. The concept of a cloud server is only applicable insomuch as it relates to a workload, not a shipping product. Companies like Calxeda and HP are chasing the idea that huge numbers of low-lost, ultra-low power servers can efficiently meet the needs of this market. Intel, as evidenced with the E5, believes that bringing functions on-die and enhancing platform level features will give it a competitive advantage. Historically, the market has favored Intel's approach; Google's own research into the subject has indicated that brawny cores are still superior to their wimpy cousins.

Intel is pushing the E5 towards the cloud because that's where the majority of growth is expected to take place in the next 3-5 years, as shown in the chart above. The E5's combination of octal cores, improved I/O, support for PCIe 3.0, and the architectural improvements that come with Sandy Bridge are a potent package; Santa Clara is well-positioned to take advantage of any corporate refresh cycles that kick off in 2012. Prices on the chips are shown below, they range from $294 for the quad-core E5-1620 to $2057 for the eight-core E5-2690.

The E5 family uses the LGA2011 socket that Intel launched last fall with Sandy Bridge-E, and as we expected, there's another two cores of creamy smoothness and an extra 5MB of L3 cache lurking in that silicon. The new Xeon platform, Romley, offers up to 24 DIMMs in total in a 2S system, supports both DDR3-1667 and low-power DDR3 1333 (1.5v and 1.35v operating voltages respectively), includes PCIe 3.0, 40 PCIe lanes in total, and operates between 70-150W. That last figure is notable because it's been a long time since Intel released a chip with a TDP higher than 140W; the E5-2687W is an eight-core, 3.1GHz part with 20MB of L3 cache. The "W" means its a workstation-only chip.

The major feature of the new E5 chips is their support for what Intel calls DataDirect I/O. Up until now, network controllers resided off-die and communicated with the CPU via the PCIe bus. With the E5, Intel has created an interface that allows the network controller to drop data directly into the CPU's L3 cache, significantly reducing communication latency. Intel claims an I/O device can read data in 230ns compared to 340ns for Westmere. PCIe 3.0 is also touted as a major advantage, though the evidence is less clear. According to the fine print on Santa Clara's benchmark results, the E5-2680 is 3x faster in a 50% Read/Write 512B benchmark when using 64 lanes of PCIe 3.0 (66GB/s) compared to an X5670 Xeon with 32 lanes of PCIe 2.0 (18GB). Given that the E5 family only supports 40 PCIe lanes, the practical benefit will be somewhat less.

Intel is pushing the E5 family as a cloud server product, which makes this an opportune time to address some of the confusion around that word. Head over to SeaMicro, the server vendor AMD just acquired, and you'll find plenty of mentions of cloud servers -- but SeaMicro's products were built around Intel Atom. Similarly, a great deal of discussion around so-called "wimpy" cores and cloud computing focuses on everything from miniscule mesh processors (Tilera) to the HP/Calxeda initiative. Now here's Intel, claiming that 95-140W chips also qualify as 'cloud' products.

This is what happens when marketing divisions collide. The concept of a cloud server is only applicable insomuch as it relates to a workload, not a shipping product. Companies like Calxeda and HP are chasing the idea that huge numbers of low-lost, ultra-low power servers can efficiently meet the needs of this market. Intel, as evidenced with the E5, believes that bringing functions on-die and enhancing platform level features will give it a competitive advantage. Historically, the market has favored Intel's approach; Google's own research into the subject has indicated that brawny cores are still superior to their wimpy cousins.

Intel is pushing the E5 towards the cloud because that's where the majority of growth is expected to take place in the next 3-5 years, as shown in the chart above. The E5's combination of octal cores, improved I/O, support for PCIe 3.0, and the architectural improvements that come with Sandy Bridge are a potent package; Santa Clara is well-positioned to take advantage of any corporate refresh cycles that kick off in 2012. Prices on the chips are shown below, they range from $294 for the quad-core E5-1620 to $2057 for the eight-core E5-2690.